In America, today as much as ever, appearance is everything. The modern American is likely to be better at spotting the brand and estimating the price of the coat a person is wearing down the street than they are at balancing a checkbook. Not only that, but the success and stature of that person will be estimated based on the price and prestige of their outfit. This American barometer of social strata, however, is completely miscalibrated when one considers that a person on the verge of bankruptcy may be able to buy a Rolex or a Mercedes thanks to the modern system of credit. This is a fact that African American musicians were fully cognizant of while living in a society that frequently portrayed dark skinned people in raggedy, hand-me-down clothes, that were often piece-meal collections of scrap-patched formal wear. In fact, these musicians recognized that dress and appearance was so essential to the society that incessantly ostracized and demeaned them, that many of the musicians found no problem in spending the majority of their cash on clothes, which were often taken out on credit. In light of this, I would argue that the increase in respectably paid work offered to African Americans in music and the opportunity to present themselves in a more respectable manner with that pay increase offered a relatively expedient pathway towards integration and acceptance into American Society. This close link between clothing and societal integration is clearly evidenced by the artifacts found in the San Diego State University special collections, such as ‘Jazz: A Visual History’ and ‘The Jim Crow Jubilee.’ The latter depicts how America attempted to display African Americans as countrified and broke before their music became mainstream (Figure 1) and the former immortalizes African American musicians as the epitome of ‘hipness’ in fine dress and fame.

Figure 1: A. F. Winnemore’s “Jim Crow Jubilee.” See Jim Crow Jubilee in works cited for higher quality image.

In order to understand the contribution of dress to the ascension of African Americans in the American social system, we must start by looking at the Jim Crow era. This time in American history is marked by a distinct fear of African Americans, especially on the part of the Southern whites that had abused and mistreated them for decades. Intimidated by the possibility of the previously enslaved becoming full fledged members of society who may, one day, pass them on the social ladder and kick them in the face, Southern whites made every attempt, socially and legislatively, to “other” the African Americans. A striking example of the social enforcement of this othering is A. F. Winnemore’s “Jim Crow Jubilee,” which was a collection of minstrel sheet music accompanied by a cover depicting “caricatures of ragged African American musicians and dancers.” (Library of Congress) In the cover to this sheet music, we can see the depiction of African Americans being centralized around their clothing, which, while fitting in the class of formal wear, is worn, ill-fitted, and mismatched. (Figure 1) This all gives the impression that these African Americans want to be as well dressed (and, by implication, as accomplished) as white Americans, but are just unable to do it quite right. This image also points to the unfavorable economic position of African Americans who, judging by the illustration, have to buy used clothes that do not fit them well and have various imperfections. This is all a consequence of the microcosm of music that produced this sheet music, which centers around the defamation of African Americans by catchy, outrageous tunes often accompanied by a dancer in black face. However, as the minstrel show waned in popularity and dignified Black art became commercially viable, we begin to see the African American caricature change form.

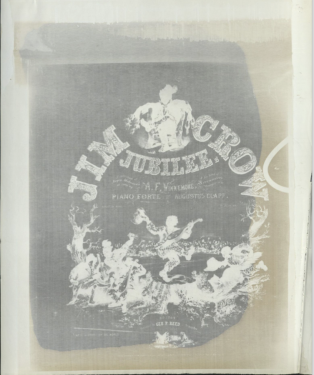

The advent of the Blues saw a paradigm shift in how America interacted with Black art. What had been disdain and ridicule towards the ‘primitive’ art that African Americans were producing turned into curiosity, and even awe towards the seemingly superb musical talents of black Americans. African American musicians, who were previously barred from using musical instruments by slave masters, found that the quasi-slavery imposed by Jim Crow continued this prohibition on musical instruments by a different means. Many former slaves were kept in a cycle of poverty in order to keep them from advancing above whites in society, which meant that they were unable to afford professionally made musical instruments. It goes without saying that a person playing a string nailed to a post wearing tattered clothing was not taken to be as serious a musician as someone with a stylish guitar and matching three-piece suit. This, however, did not keep them from creating music, as many different forms of homemade instruments began to crop up. Ethnomusicologists such as John Lomax began to take note of these people playing homemade instruments and conducted ethnographic research across the rural south, studying the folk music of African Americans. Lomax was particularly interested in prison music and, as a result, discovered musicians such as Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter who achieved some degree of commercial success as a result of Lomax’s research. The most important aspect of this research is that John Lomax believed, according to an interview with his son Alan, “Leadbelly… was an example of a great American artist and he presented him in the North as that.” (Baldry 2001, Track 17) That is, Leadbelly was not treated as a curiosity or ‘sideshow freak’ for the entertainment of judging whites, but instead he was an “amazing fellow who had an amazing American experience,” regardless of the color of his skin. Berendt clearly felt the same in regards to early Blues musicians such as Leadbelly or “Blind Lemon” Jefferson as he chose to display them in his book, “Jazz: A Photo History,” later in their lives when they were well dressed and presentable. He could have easily, as prior historians of the blues have, displayed them with their prison mugshots taken when they actually created their music and played into the narrative that they were dangerous and strange men. Instead, he chose to commemorate them as capable and respectable musicians, with professionally made instruments and tailored suits on stage, just as Lomax attempted to do. It is this kind of work that humanized African Americans through art and prepared the rest of America for the next steps in integration. (Baldry 2001, Track 17)

Figure 2: Photograph of Leadbelly later in life, looking well dressed. (Berendt 1979, pg. 49)

As the blues spread across America and enjoying African American music became more widespread and acceptable, forms other than the Blues began to crop up and gain traction. The problem with early Blues, as it pertains to the advancement of African Americans, is that it was still seen as a sort of novelty act to most white Americans. Due to the low quality of recording technology, musicians (or Songsters, as they referred to themselves as) were forced to yell into the recorder and ended up sounding ‘wild’ and ‘uncultured’ in their art. Unfortunately, this “shouting” Blues was the only type of black music that most whites heard, as this music could only be found in the rural south and most listeners were in the metropolitan north. This, however, would all change when a new sort of music called ‘Jass’ (later changed to Jazz) began gaining traction in the big port city of New Orleans. For the first time ever, black musicians found steady work in the red-light district, presenting them with enough cash flow to buy professionally made, European instruments and clothes fit for a respectable performer. Trumpet, Piano, Guitar, Bass, Trombone, and Clarinet, all instruments familiar to white folks from European classical music, were now presented to them in an entirely new and exciting way. A musician of particular importance to this time period was the Great Louis Armstrong who, like many others, honed his chops in New Orleans before joining the great migration to the northern city of Chicago. While the cash in New Orleans’ red-light district presented opportunities not found at any other time to black Americans, it was dwarfed by the enormous amount of commercial success Armstrong found in the densely packed Chicago nightclubs. Armstrong was able to dress well, rent a nice apartment, eat well (as evidenced by his massive weight gains), and even had enough cash left over to entertain himself and his wife on the weekends. It could be argued that the key thing enabling this success in Armstrong’s case, but not in the case of the early blues musicians, is that Armstrong looked the part of a dignified musician in every way but the color of his skin. When white society saw a man in a fresh, clean suit with polished shoes playing a shiny brass horn (which could be thought of as an accessory to his outfit in this case), they were willing to look past his race just enough to enable his popularity and ensuing financial success. This is clearly a fantastic leap from how an African American could expect to live ten years earlier, but Armstrong was part of a tiny minority. Due to his immense talents, he was able to gain the requisite fame and money to afford these various creature comforts with cash out of pocket, but most aspiring musicians and factory workers couldn’t dream of such monetary success. The thing that continued to set Armstrong apart from the crowd was that he possessed a reputation of fame and when people came to see him, they saw a well groomed, well dressed, black man with a shiny horn. In other words, Armstrong looked the part of someone deserving of fame. This had an impact on both black Americans who saw him as a beacon of hope proclaiming that they too could reach such a status one day, and white Americans who were more easily convinced of Armstrong’s worth as an artist by seeing how well he presented himself. Armstrong would maintain and grow this image for his entire life, leveraging it to push civil rights and the popularity of his music. However, as I mentioned before, Armstrong was part of a distinct minority, and many African Americans would have to push much harder and wait much longer to reach such a high status.

Be-Bop, which was the natural antecedent to Armstrong’s generation of Jazz, saw a complete shift in the culture of black music. Those musicians who were forced to push harder and longer to reach Armstrong’s social stratum, began to get fed-up with waiting, especially after many of them served in World War II and returned home to the same anti-black America they left to fight for. This was reflected in the hastened pace of the music, the more aggressive sounds, and the completely fresh ideas. Music was not the only thing hastened by this shift in culture, spending habits also saw a massive shift in this time. Malcolm X, a contemporary of these musicians, recalls in his autobiography that his father believed, “Credit is the first step into debt and back into slavery,” which was representative of the opinion of many black Americans at the time. (Haley and X 2007, pg. 21) Even young Louis Armstrong had to toil for months to scrap up the few dollars it took to buy a beat up cornet from the pawnshop near his home, either not wanting to or not being able to take advantage of credit. Malcolm X, however, quickly turned to credit when he wanted to fit in with the slick, urban New York City crowd by buying a very expensive Zoot Suit. He first tried to save, but it was taking too long and upon speaking to a friend, he was set up with a line of credit at a tailor. After receiving various ‘gifts’ for overspending on the suit since no payment was due upfront, Malcolm X said, “I was sold forever on credit.” (Haley and X 2007, pg. 44) The musicians were also fond of credit by the time of the Great Migration and began to not just adopt the dress that white people thought looked sharp, but became the trendsetters of urban style. In fact, white Americans began to emulate the style of these black musicians, especially in the case of Dizzy Gillespie. Dizzy’s trademark beret and glasses became the hottest item in town, and troves of adoring white fans came to his shows in full Be-bop uniform to meet him. (Figure 3) This inferred a social status to Dizzy that he did not squander, as he was outspoken about civil rights, and the young white Americans who adored him were listening. Gillespie once said, “The Enemy, by that period, was not the Germans. It was above all, white Americans who kicked us in the butt every day, physically and morally… If America wouldn’t honor its Constitution and respect us as men, we couldn’t give a shit about the American way.” (Burns and Ward 2001, pg. 305)

Figure 3: Dizzy Gillespie signing autographs for white fans. (Boina, 1970)

Armstrong himself was not pleased with the aggressive path taken by the Be-boppers, as he felt it threatened everything he had fought to build towards civil rights. In quietly subverting American cultural norms of racism over his multi-decade career, Armstrong achieved an integrated bandstand, some level of political influence, and was even allowed to eat at white restaurants and sleep at white hotels with the band. The more overt tactics of the Boppers seemed, to Armstrong, to be destined for conflict and failure.

This conflict in methodology between generations of minority populations was not isolated to African Americans. In fact, around the same time, Mexican American families were concerned about their sons and daughters becoming Zoot Suiters, or Pachucas/Pachucos. Similar to Armstrong and other older African Americans, many Mexican Americans families were worried that the Pachuco dress (and the behavior that accompanied it) was damaging to the work they had done to improve their place in American society. In her paper Crimes of Fashion: The Pachuca and Chicana Style Politics, Catherine Ramirez argues that Mexican American children’s dress and associated behavior, “… Appeared to privilege individual desires over the family’s survival (as well as the nation’s survival).” (Ramirez 2002, pg. 12) In wartime, this meant that Mexican Americans were not contributing enough to the society in which they were living and gave the white middle class further reason to ostracize and other the minority population. A similar connection to the war happened in the clash between generations of African Americans. Those who belonged to the older generation, such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, were integral to the war effort in selling bonds and rallying morale. The younger generation, such as Gillespie and Coltrane, were being asked to fight in a war for a country that frequently disrespected them, and they let everyone know how they felt about it (as you can see in Gillespie’s quote above).

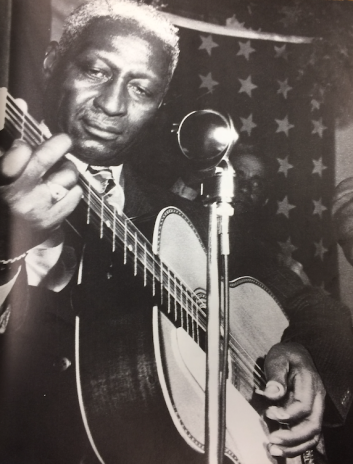

This trend relating social integrations, music, and dress did not end with the be-boppers of the late 1940’s and 1950’s. By this time, black music was a hallmark of American culture and was there to stay. Knowing this, musicians continued to act as trend-setters of both art and fashion, using their art to make political statements as well as their dress to maintain their popular appeal. In 1960, legendary drummer Max Roach released an album in response to the sit-in movement entitled, “We Insist!: Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite.” This album is considered to be a hallmark Jazz album, as it was one of the first to make a bold and powerful political statement concerning the treatment of dark-skinned people in countries where they are “free” by law. Roach relates the experience of slavery in America and apartheid in South Africa to the paradoxical form of freedom experienced by modern descendents of the enslaved and systematically abused. This and the then provocative cover image set the stage for following generations of Jazz musicians to make bold political statements despite potential backlash. (Figure 4) A more modern example, for instance, is Wynton Marsalis’ “Black Codes From The Underground,” which deals with issues such as disproportional incarceration rates amongst black men. Works such as these are clear indications that black music in America has been used as a conduit for social change along side the ongoing civil rights movement.

Figure 4: Max Roach’s “Freedom Now Suite” album cover depicting 3 black men participating in a sit-in. (Roach, 1960)

When taking this whole discussion into account, it is clear to see the relationship between dress, art, and social change in America. While it is irrefutable now that early titans of black music were fantastic artists regardless of race, 20th century America was hardly ready to recognize a dark-skinned man as capable of anything beyond primitive art. We see evidence of this with early blues songsters such as Leadbelly, who, in his time, despite being a world class musician, was not recognized as anything more than a poor, countrified black man performing a novelty act by anybody but a select few Academics. It would take the work of those like Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong who, recognizing the fact that he would appear as a countrified square from New Orleans, went to great lengths to ensure that he looked “right” on stage with a fresh, clean suit, polished shoes, and a shiny brass horn. By presenting himself in the way that society expected from a great musician, Armstrong was able to subvert cultural norms surrounding race and rack up both fame and cash that would allow him to continue impress all Americans with his art. This set the groundwork for a lineage of black musicians who, like Armstrong, would use their platform to affect social change in both subtle and direct ways. The difference in Armstrong’s descendants was that they no longer had to bend to exactly how society wanted them, instead they could bend society back. In other words, African American culture did not just have to integrate into American society, American society also had to integrate into African American culture. Fashion and music, two powerful forces in popular culture, were now strongly influenced by the stylings of African Americans who finally cemented their place in American society through the humanizing force of music and culture. Evidence of this progress is clearly displayed in the San Diego State University Special Collections, which contains primary sources such as ‘Jazz: A Photo History’ and ‘A.F. Winnemore’s Jim Crow Jubilee,’ that show the shift in American Society’s perception of African Americans after they were able to take control of their own image through music and dress. While African Americans were displayed shamefully in minstrel shows such as the ‘Jim Crow Jubilee,’ Blues music, followed by a continuum of African American music including Jazz, provided a way for African Americans to take control of their own image. Slowly but surely, these musicians changed society to the point where a book such as ‘Jazz: A Photo History’ could be published, which displayed these musicians and their art as dignified and deserving of admiration. It is hard to imagine the social progress that we have arrived at in 2018 would be possible without the work of these brilliant musicians and the Academics who were willing to give them a chance.

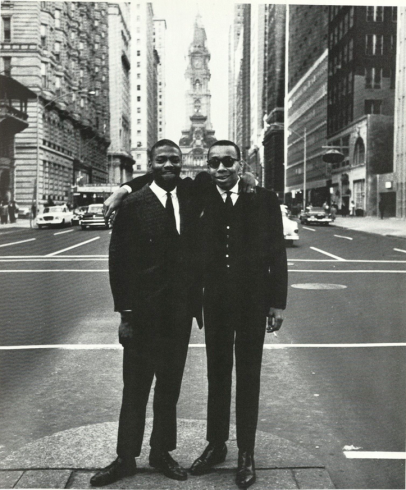

Figure 5: Lee Morgan (right) exemplifying the stylings of his contemporaries in thin suit, shined shoes, and “be-bop glasses” (similar to modern “Ray-Bans”)

Works Cited:

Primary Sources-

(All primary sources courtesy of the San Diego State University Special Collections)

(ca. 1847) Jim Crow Jubilee. , ca. 1847. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001701399/.

Berendt, Joachim Ernst. Jazz, a photo history. Schirmer Books, 1979. pgs. 49, 213

X, Malcolm, and Alex Haley. Malcolm X. Guardian, 2007. Pg. 21, 44

Secondary Sources-

Baldry, Long John. Remembering Leadbelly. ALAN LOMAX – Interview – “Remembering Leadbelly”, Stony Plain Records, 2001, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1sunjBFy5XY. Track 17

Boina, Beret And. “The Beret Project.” Dizzy Gillespie, 1 Jan. 1970, beretandboina.blogspot.com/2011/07/dizzy-gillespie.html.

Ramirez, Catherine 2. Crimes of Fashion: The Pachuca and Chicana Style Politics. Indiana University Press, 2002. pg.12

Roach, Max. We insist! Max Roachs freedom now suite, 1960.

Ward, Geoffrey C., and Ken Burns. Jazz: an illustrated history. Pimlico, 2001. pg. 305