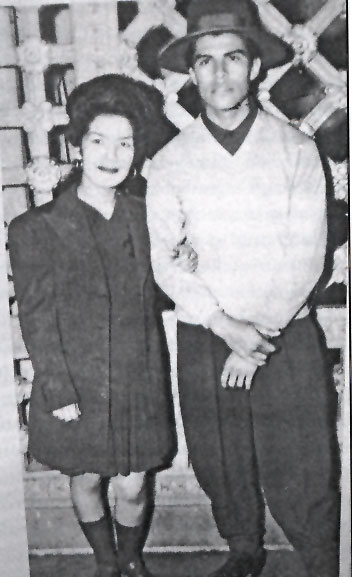

The pachucas (female zoot suiters) and flappers both fulfill a cultural trope of the 20th century– youth rebellion through fashion. Youth in this century at different times in many different cultures felt a need to rebel against their parents’ generation and society in general. In this way the zoot suiters and flappers were very similar. They both wore their hair and dressed in very provocative ways, which caused a great deal of conflict as well. The new racy clothing and hairstyles served several purposes. For both pachucas and flappers the new style emphasized their new take on female sexuality, showing that they were more open and free to sexual acts, not as much constrained by the rigid social structures of the past. These new styles also represented a political statement, which in each case differed a bit, but was largely the same. It was meant to illustrate women’s strong and growing desire to become more involved politically. The new style showed that they were fierce, strong, and willing to take charge if they were not given more chances to participate. The author of “Crimes of Fashion,” Catherine S. Ramirez, describes the look of the pachucas as “loud” and “excessive” when viewed by members of the middle and upper class. The new dress of the pachucas was startling for these people and to older Mexican Americans in general, as it made them worry other Americans would think all Mexican Americans would act in the same way. This was one main difference between the pachucas and the flappers: the pachucas had their race to carry with them as well. The flappers did not have to worry about other Americans viewing their race differently or perpetuating pre-existing racial stereotypes that might apply to them, they mostly had to focus on the gender conflicts they caused.

References: “Crimes of Fashion: The Pachuca and Chicana Style Politics” by Catherine S. Ramirez